I reviewed my build journal recently, and found enough themes in there for another bit of bloggy catharsis. No one should mistake this as the advice of an expert in anything, as I have a long way to go before I start collecting karma points at the playground. But at least I can claim that these ideas are well tested, because as the saying goes, I never make the same mistake twice – I make it 5 or 6 times… just to be sure.

Prototyping:

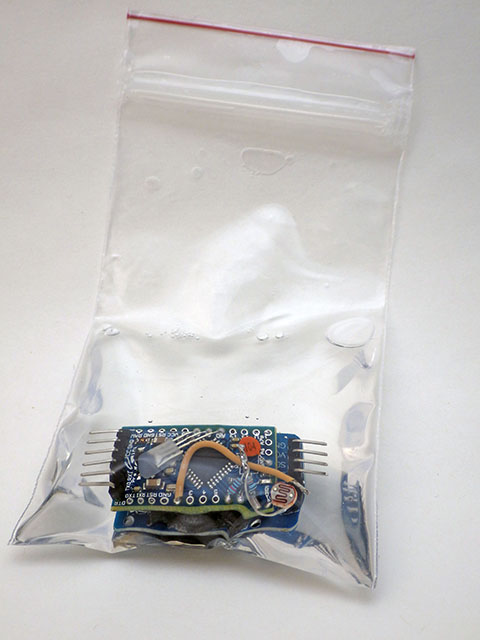

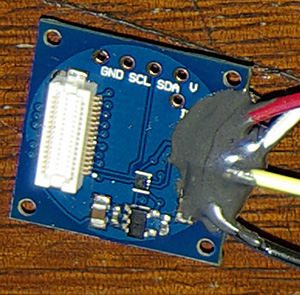

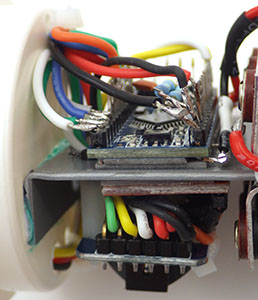

Only RTC, SD, & interrupt lines soldered to the mcu.

Join the forums: Everyone says read the datasheets first….well from this beginners perspective that’s B.S. Even when I started to understand all the terms I was reading, it was still a major leap of understanding to realize what the information in the data sheet implied… (and I still go through it with each new sensor) If you want to get rolling on something start with the discussion forums, because it’s likely that someone there has already walked down your path, or one very close to it. Thirty minutes Goggling Sparkfun, Stack Exchange, or searching through places like the Arduino Playground, will get you farther than several hours reading the datasheet. Of course you will eventually end up doing that too...just don’t start there. Often the forums lead you to some well commented GitHub code examples. It is so much easier to understand the data sheet, when you have a piece of relevant code in front of you at the same time. Datasheets are written solely for corporate electronics engineers, because unless you represent the 10 to 100 thousand unit MOQ, you simply don’t show up on company radar.

( Sometimes it even seems that a company deliberately tries to hide the functions built into their own ICs from the maker community. For example: the mysterious Digital Motion Processor (DMP) functions of the invensense 9150. I have yet to find a single example of an Arduino script accessing these features though the 9150 is commonly used in quad copters. I’d have thought that having Euler angle & 9DOF quaternion calculations done for free, would have drawn some serious attention from those those guys.)

You need one completely “trusted” set of kit: Which you will pay dearly for, but you need it to test out each new component you are thinking of adding to your project. (I still haul out my original Uno for this from time to time, because the darned thing is virtually indestructible…)

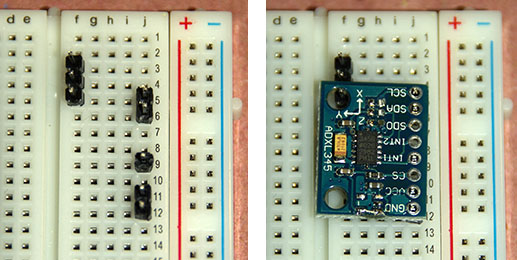

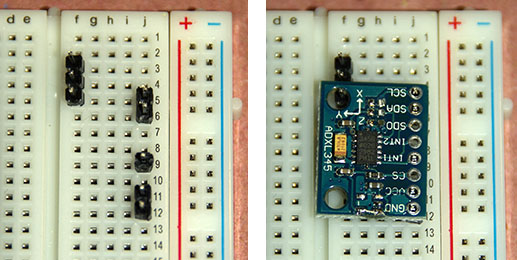

About 1 in 10 of the cheap eBay boards are D.O.A. This ADXL345 board had a pretty typical alignment skew: X & Y axes were ok, Z did not read.

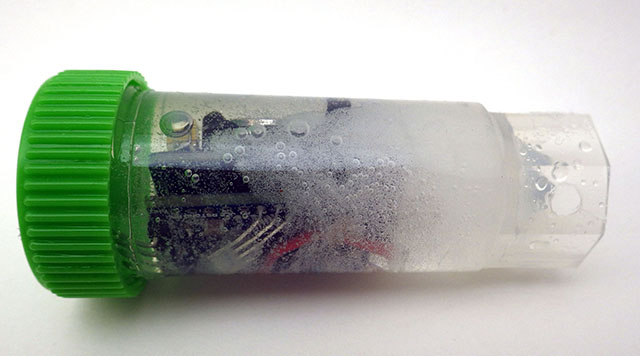

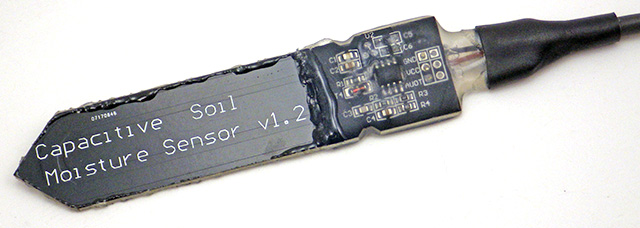

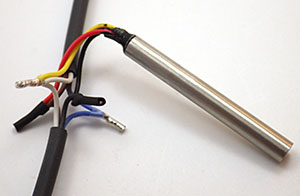

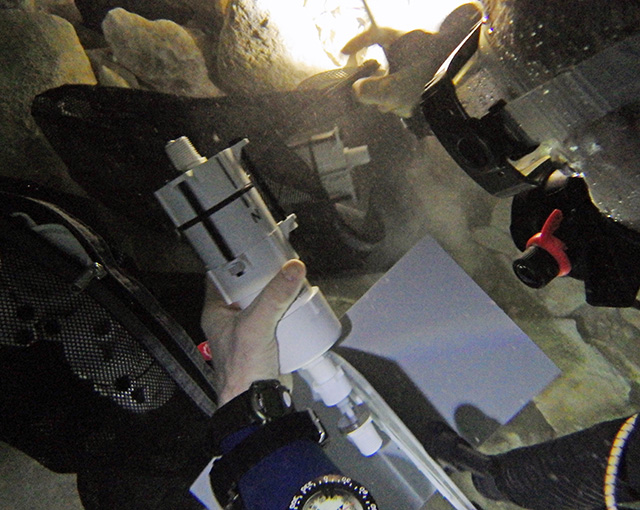

Connect new parts one at a time: Do not add to your grief by connecting two new untested pieces of equipment to each other at the same time. (like, for example, a new FTDI board, and an Arduino clone of off eBay….grrrrr….) I am slowly learning what it is that you are paying for when a given sensor module sells for $20 from a trusted source like Sparkfun and $2 from China. It’s probably not the components (although I hear there are fake IC’s out there) but something else that’s just as important. If you watch the Tiny Circuits promo vid, around the 5 minute mark you see a person manually re-positioning the components that the pick and place machine laid down, and then around 7:15 you see someone testing each board before shipping. At this point I have seen enough of the eBay stuff that I am pretty sure that these two steps are never done on the clone boards. So If you go down that route, you are implicitly agreeing to do those jobs yourself (in addition to cleaning off all the excess flux left on the boards…) This is not a problem when I am just hacking something together, and then testing it on the bench (or in the bathtub…) but not a risk I will take lightly for the fieldwork units.

And while we are on the topic of those cheap modules, they almost always arrive with connections broken out for both SPI and I2C, but you will likely use them as one or the other, meaning that you often need non adjacent pins soldered onto the breakout. I used to fiddle with crappy metal “helping hands” things (now replaced by a far more effective Panavise Jr) to get those single pins soldered into place, but now I simply use a bread board to hold the pins in the correct locations before soldering:

Many thanks to my bother for showing me this soldering technique!

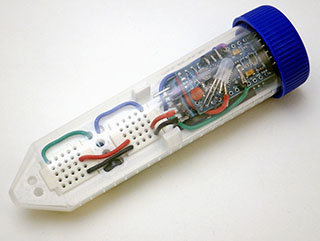

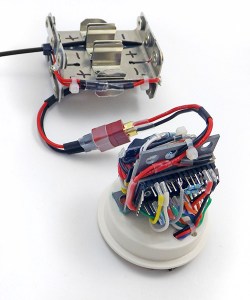

Modularize your designs: Breadboards were never very practical for me because most of my projects get bashed around, and are supposed to run while the whole thing is in motion. But even after the prototype stage my sensors are not usually soldered directly to the data loggers. Yes, it’s a pain constantly making custom all those custom interconnect cables, especially since I color code everything – I2C bus, interrupt lines, …everything. And once you get an early prototype working, immediately build another one, and do all of your tests, etc., on the second unit, with the first working unit just sitting on the shelf. Then if something stops working, you can use process of elimination with the known good modules to isolate the cause of the problem quickly. Often this technique helps me identify that the problem is actually in the software, and not with the hardware at all. But I am still wading my way through the wonderful world of crimp connectors for ones that will prove robust enough for fieldwork. (note: I’ve adopted Deans Micro Plugs for my current builds…)

Coding:

Hit the verify button often, even when you make “simple” changes: Don’t wait till you have been working for half an hour because humans can only remember 7±3 things (for this human, even less than that…) You will be backtracking allot and error messages in the AVRc programming environment are usually about as helpful as a baby crying. You know something is wrong, but often you cant figure out what the problem is from the feedback it give you. Something as simple as: “Hey man, you left out a semicolon at the end of line 17” can be reported with anything from a one line “Expected X before Y” error to twenty (or more…) lines of cryptic compiler faults. Sometimes Google is your only friend when this happens.

The utility of a piece of code is directly proportional to how dangerous it is to use: For example: Global #define statements are tricky…especially when you are using libraries, because you never know when you have tried to “re-define” something hidden in one of those libraries. Interrupt handling is another example of something tremendously useful, and really easy to screw up when you have more than one sensor generating interrupts in the same piece of code, at the same time.

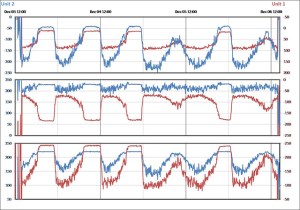

Software faults almost always show a repeating pattern of behavior: At least that’s been my experience so far. Bad wiring, or some other issue with the physical build, (like a v. regulator thermaling out…) hangs the system in a way that is much more unpredictable. Of course, finding those patterns is a heck of a lot easier when your project is a data logger in the first place…

Physically putting “stuff” together:

Third time’s a charm: If your alpha works at all; that’s a great success. The holes will be in the wrong place, you will use too much epoxy, and it will be a clunky octopus of dodgy wiring. But even if it only runs for a single day, it has done the job of showing if the idea will work. (and they make such stylish book-ends…right?) The second build lets you sort out the right physical locations for all the components, and eliminates that hour of laborious hand-sanding that you really did not need to do. This is also the model that lets you work out most of the software bugs, because it is usually much easier to open & close without breaking fragile jumpers all the time. But for me at least, it’s the third build that usually comes together in a way that feels right.

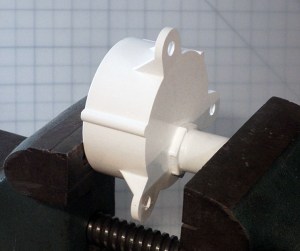

This type of bench vise is handy. I picked this one up for $10, at a garage sale and it has been fantastic for holding parts together while epoxies cure & solvents weld.

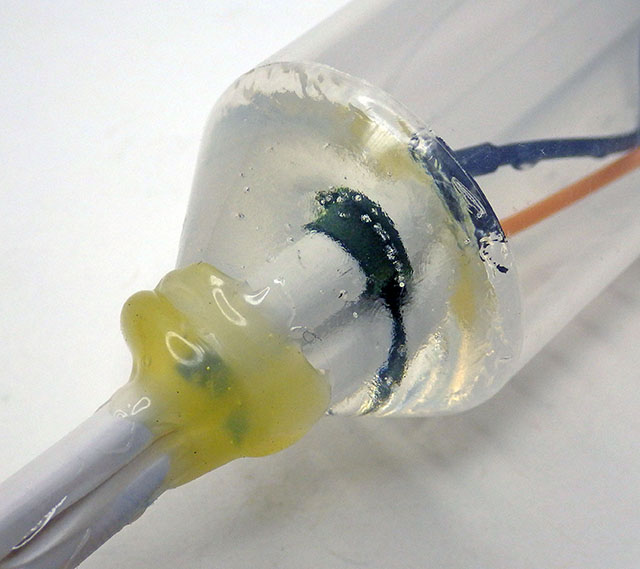

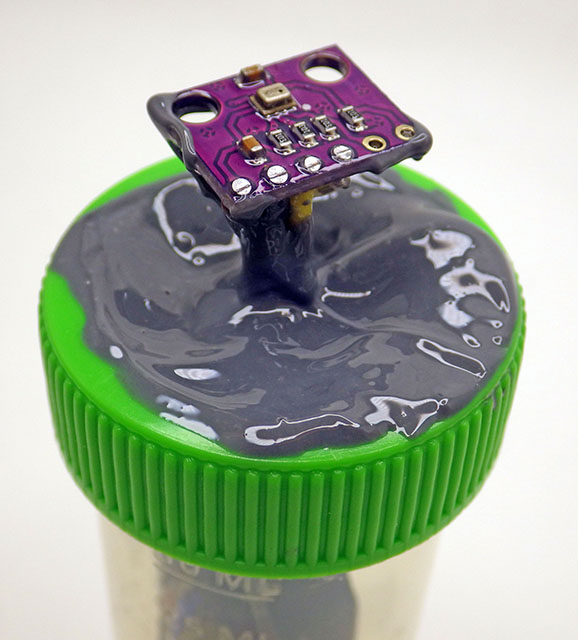

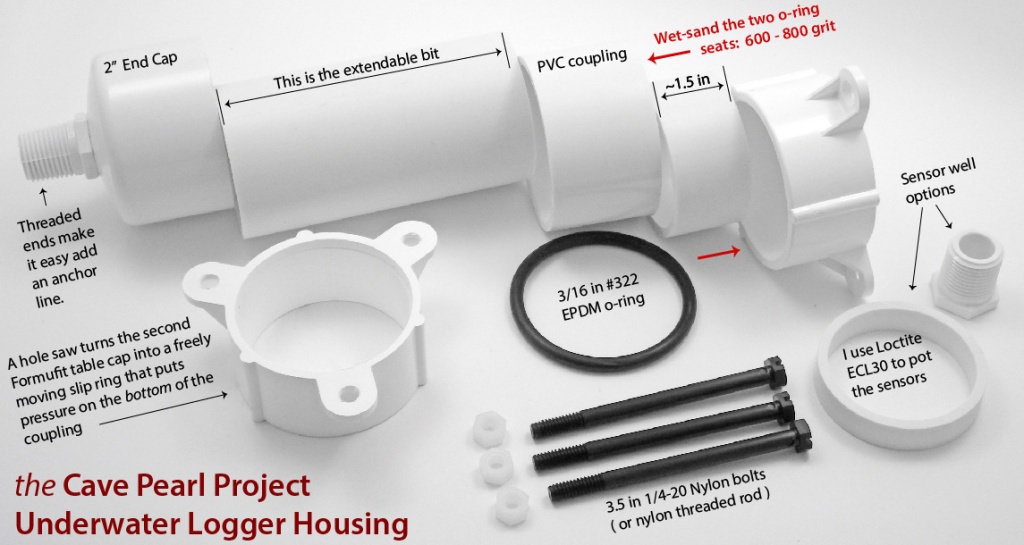

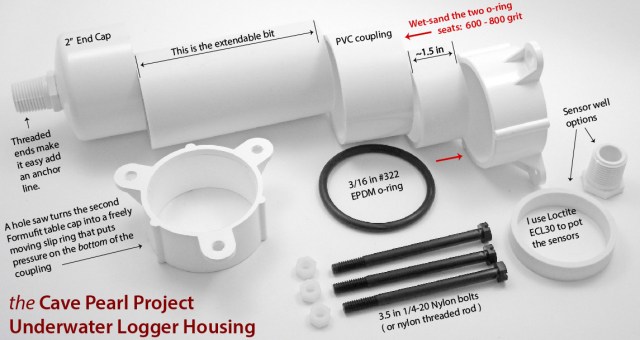

Adhesives & epoxies can be one of the most expensive components in your physical build: (I wasn’t expecting this one) I go through a fair bit of Loctite E30-CL (or E00CL for better PVC bonding) for my hull pen-etrations, and I love the fine control of the applicator gun. But the mixing nozzles alone are more than a buck each, and they are elegantly design to waste a large volume of that precious epoxy with every use, which then solidifies inside the nozzles turning them into expensive single use devices. That irritated me enough to start experimenting, and it turns out that Goof-off (mainly xylene, and 2-ethanol) cleans out those applicator nozzles relatively easily. (Acetone would also work) I usually buy my adhesives from Zoro Tools. (note: their product search function is terrible, I use Google Shopping to hunt for stuff on Zoro’s site) There are plenty of cheap Loctite sellers on eBay, but many are hawking expired lots. In a pinch, I fall back to good old JB weld, and I use PlasticWeld putty absolutely everywhere because it nicely adheres sensor boards to both PVC & ABS in a way that is strong, but still removable (sort of..) if you have to repair something. Be careful not to bridge contacts with your adhesives on really sensitive sensors. Most of these epoxies do not conduct electricity, so I use JB weld to shore up weak jumpers on I2C lines all the time. I have had problems with some sensors not working after gluing, probably because the cured epoxy added capacitive effects to the circuits. I have also started experimenting with 3M’s VHB double sided tape (for low surface energy plastic & acrylic substrates) to see if that is easier to work with. (Note: after testing the VHB did not work as well on the pvc as the standard 5lb mounting tape)

(…and if paying an “arm and a leg” for your adhesives wasn’t bad enough, those cheerful, brightly colored labels hide some fairly dire warnings about skin contact literally causing cancer, or vapors so dangerous that use of the product anywhere other than a open field is guaranteed to give you brain damage & significantly harm your … uhhh … “reproductive capacity”. Don’t believe me? Get a 200x microscope and read that fine print for yourself… just make sure you do it some place far away from stoves, heaters, electric motors and all other sources of ignition…like soldering irons 🙂 )

The shop course that you only took in high school to boost your marks will finally start to come in handy: Turns out that working with PVC is almost the same as working with wood, so I was surprised by how much time I spent scoping woodworking forums while figuring out how to cut weird angles and then re-assemble things.

An angle grinder pulls the rust off of old school tools in short order.

You can build anything with three pieces of “iron”: A good soldering iron, a drill press, and a 13″ bench top scroll saw (which cuts PVC and trims circuit boards beautifully). I have not regretted for one second putting down $100 for my little Haiko from Adafruit. (Wish I had bought the thing at the very start of this adventure.) But my other two irons are vintage Sears Craftsman models which cost next to nothing because when I bought them, they looked like flea-market clunkers from the days before plastic was invented. Cleaning them up was worth the effort because they weigh a ton, and are rock solid stable. In fact, these days I actually go out of my way to get old tools for my workshop. So if you see me one morning, at yet another garage sale, don’t be surprised if my hands are full of weird drill bits, strange clamps, and other rusty lumps of metal that are even older than I am.

And last but not least:

I know everyone has their own taste, but I find that Pandora’s “Chillout” channel (in the Dance/Electronic genre section) just has a really good vibe for working on the bench. Spacey electronica wallpaper-music smoothly delivers the hyper focus I need to sustain a long soldering session, especially when the clock ticks on into the wee hours… .

Addendum 2014-07-29

I have another one to add to this list but it stands outside of any category because it seems to apply equally. I call it the ‘Principal of Equivalent Annoyance’, and it’s just the observation that the dumb little things on a project take up at least as much time as the big important things. For example: when you connect allot of parts together, the physical behavior of your wires matters more than you’d expect because the difference between good insulation and stiff hard plastic puts quite a bit of pressure on the wires when you fit everything into the housing. Once and a while I am left with some excess lead wire from a sensor and when I open up the left over multicore cable I sometimes find a meter or so of the perfect wire. Soft silicone insulation, 12 or more strands, no tinning… the stuff is fantastic to work with and is so flexible that it doesn’t stress the connections. Of course it never has any identification marks on it that might lead me to the source. So I am slowly working my way through every brand of hook-up wire on the market, searching for this holy grail, and wasting more time on it than I even want to think about. I suspect this is kind of thing happens on every project.

Addendum 2014-09-13

There are a few contenders so far in my ongoing search for “the perfect wire”:

Adafruit sells 26AWG in multiple colors. This is my current favorite wire because they sell it in easy to handle packages (~0.95/2m) and they have the only grey & orange colored stuff I have found so far. It probably sounds silly to mention the packaging, but from other vendors like Hobby king, or eBay, you can expect to spend at least an hour untangling the spaghetti when your wire arrives. Their 30AWG is 0.70/2m, and is very handy for running jumpers across the surface of a breakout board.

Sparkfun sells their red & black silicone hook up wire at a good price, I just wish they had more colors.

Cal Test Electronics CT2956 Test Lead Wire: (24awg $9 for 10 m, green, white) It is soft multi-strand bare copper and there is some variability in the stiffness as they seem to use different stranding depending on the color you order, but all of it is much more flexible than pvc insulated wire. The insulation is nice and thin, so it crimps well into the standard 0.1″ connectors, and it is a bit stiffer than the Turnigy, so it will hold a bend you put in the wire.

Turnigy Soft Silicone Wire: (24awg $.60-$1 per meter, red, black, yellow blue) which is popular in the RC plane/Quadcoper crowd. Multi-strand “tinned” copper, with lots of colors. The very soft insulation is about twice the thickness of the Cal Test, but it still crimps nicely. (note: Hobby King does not let you mix warehouses on orders…)

There are two drawbacks to to using really soft silicone wire: You can not push the female crimp connector ends into the housings as you normally would with jumper wire. You have to dig in and pull the connector through the enclosure with tweezers. The other issue is that because the silicone conducts heat so much faster than pvc, you will burn your fingers more often while soldering if you are not careful. In return, you can stuff as much spaghetti as you want into a very tight housing without putting pressure your the solder joints in the process. The wire stripper from Pololu, works well on both types of wire.

Addendum 2016-03-11

More eBay vendors for silicone jacket wire are appearing over time, and they are a great place to find a wider selection of colors like brown, purple, & pink. With module & jumper builds like mine, you need as many different colors as you can get your hands on.

Addendum 2015-01-09

I received a 10″ craftsman 21400 band saw for Christmas this year. And just like the night & day transition that occurred when I went from a crummy soldering iron to the lovely Hakko, my cuts have now become more accurate and virtually effortless. No more risking my fingers trying to cut pipe on the table saw! And free-handing with a band saw accomplishes 90% of what I could do with the the jig saw as well. If you can only afford to own one cutting machine, then I am now convinced it should be a bench-top band saw. Wish I had it from the beginning…

Addendum 2015-01-16

Looks like I am not the only one who is irritated by the waste generated by the Loctite 50ml nozzles. The folks over at RCuniverse confirm that acetone makes a good solvent for cleaning out the mixing tubes, and that its easier to do if you remove the white plastic mixing baffles first. They also mention that putting the nozzles in bags in the freezer will prevent the epoxy from setting, so I might try this trick to see if I can get the tubes to “self clean” by gravity. Looks like All-Spec is the cheapest source for the nozzles, but I keep finding “generic” mixing nozzles on eBay that claim they work with both 3M and Loctite adhesives. Haven’t tried them yet though.

Addendum 2015-02-02

I bought some of the cheep MA5.4-17S 17 element mixing nozzles, and although the fit perfectly onto the 50ml dispenser, they were much shorter than the 15cm, 20 element, Loctite 98623 nozzles I usually use:

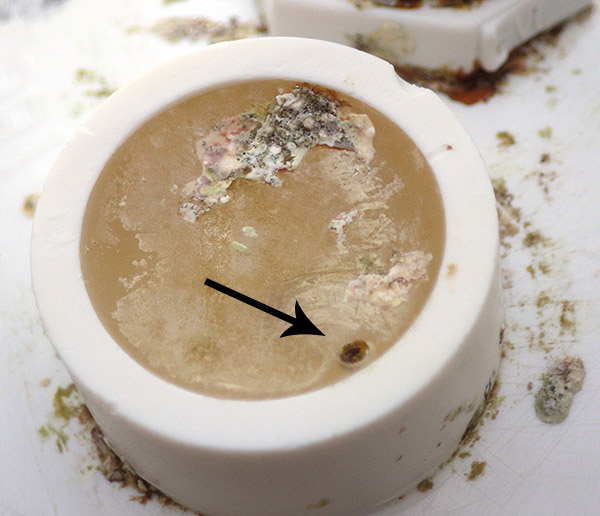

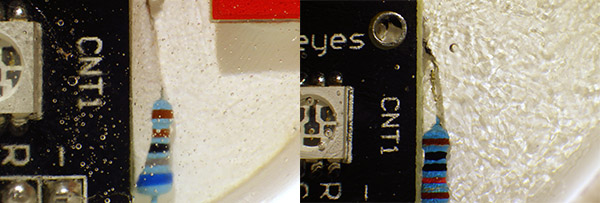

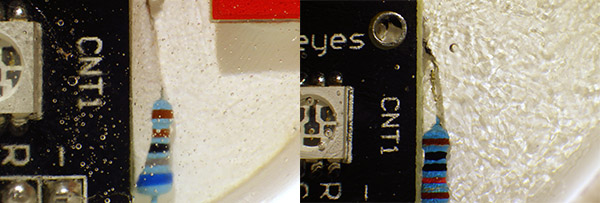

I thought this was a good thing, as I hate wasting all the epoxy that is left in the dispenser after every use and these smaller ones only retained 1.68ml in the barrel. I did some test pours under nearly identical conditions, and the smaller nozzles left a significant “swirly” pattern when the cured epoxy was examined close up a few days later:

Left side: Loctite Nozzle Right Side: Short MA5.4-17s nozzle

I am interpreting this as a density gradient formed by inadequate mixing in the shorter nozzles. The epoxy has still set hard as a rock so I am not sure if this compromises the integrity too much. There are also listings for MA6.3-20S and MA6.3-21S nozzles, and I will try some of those next time.

(Note: the MA6.3’s worked great, as did the $10 applicator guns on eBay)