This post describes a thermistor calibration achievable by people who don’t have access to lab equipment with an accuracy better than ±0.15°C. This method is particularly suitable for the 10k NTC on our 2-module data logger handling them in a way that is easy to standardize for batch processing (ie: at the classroom scale). We use brackets to keep the loggers completely submerged because the thermal conductivity of the water around the housing is required or the two sensors would diverge. The target range of 0° to 40°C used here covers moderate environments including the underwater and underground locations we typically deploy into. This method is unique in that we use a freezing process rather than melting ice for the 0°C data point.

Reading a thermistor with digital pins uses less power, and gives you the resistance of the NTC directly from the ratio of two Interrupt Capture Unit times. Resolution is not set by the bit depth of your ADC, but by the size of the reservoir capacitor: a small ceramic 0.1µF [104] delivers about 0.01°C with jitter in the main system clock imposing a second ‘hard limit’ on resolution at nearly the same point. Larger reservoir capacitors increase resolution and reduce noise but also take more time and power. The calibration procedure described in this post will work no matter what method you use to read your NTC thermistor.

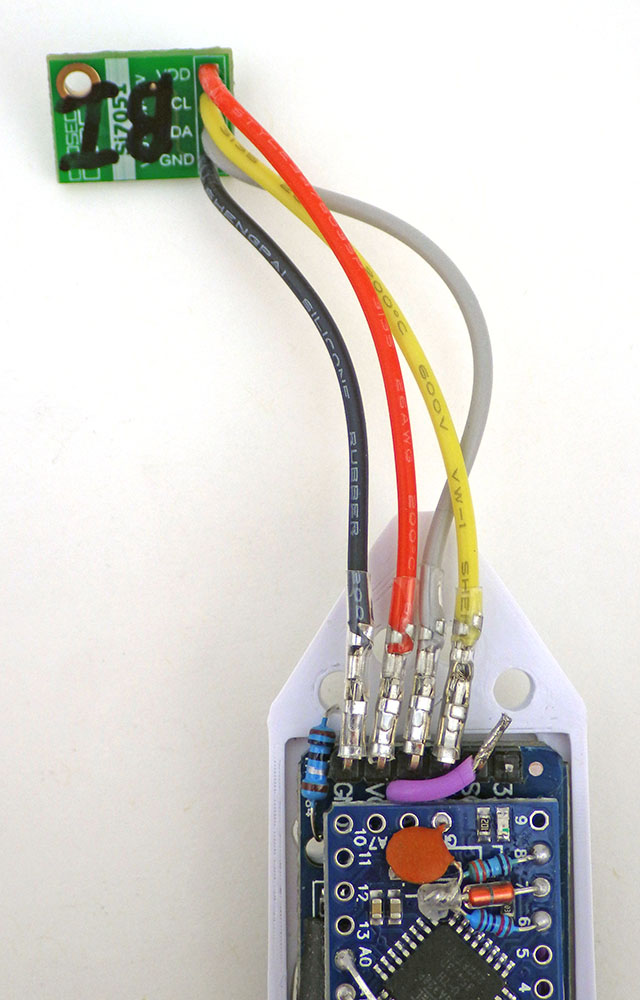

Off-the-shelf sensors can be used as ‘good enough’ reference thermometers provided you keep in mind that most accuracy specifications follow a U-shaped curve around a sweet spot that’s been chosen for a particular application. The Si7051 used here has been optimized for the medical market, so it has ±0.1° accuracy from 35.8 to 41° Celsius, but that falls to ±0.13° at room temperatures and only ±0.25° at the ice point. If you use some other reference sensor (like the MAX30205 or the TSYS01) make sure it’s datasheet specifies how the accuracy changes over the temperature range you are targeting with the calibration. We are patiently waiting for the TMP119 modules to become available with a typical accuracy of ±0.03°C from 0°C to 45°C (although if you dig in to the datasheet they later spec a max of ±0.08°C). Whatever module you use it’s a good idea to remove I2C pull up resistors and any onboard LED as these can dissipate sufficient power in the vicinity of the sensor to cause deviations. One shot modes avoid the sensor self-heating issues you often see in continuous operation modes, and increasing the number of conversions being averaged per shot can help the accuracy of your reference.

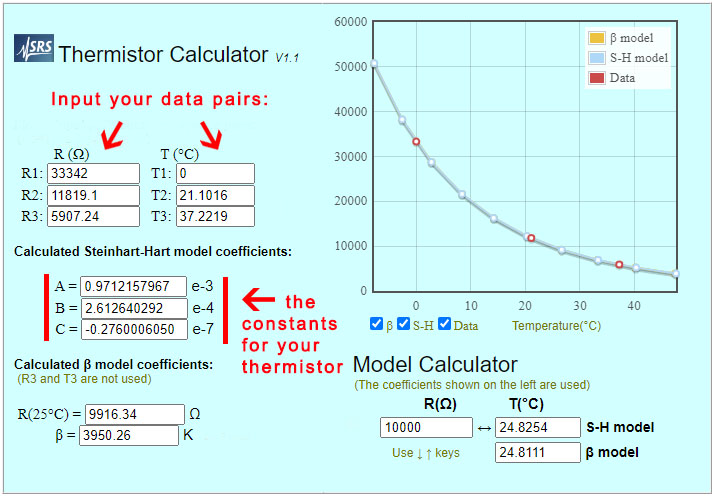

The shortened Steinhart–Hart equation used here is not considered sufficiently accurate for bench-top instruments which often use a four or five term polynomial. However in ‘The Guide on Secondary Thermometry‘ by White et. al. (2014) the three-term equation is expected to produced interpolation errors of about 0.0025°C over a range from 0 to 50°C, and that is acceptable for most monitoring. To calculate the three equation constants you need to collect three temperature & resistance data pairs which can be entered into the online calculator at SRS or processed with a spreadsheet.

While these technical sources of error limit the accuracy you can achieve with this method, issues like thermal lag in the physical system and your overall technique are more important. In general, you want each step of the calibration process to occur as slowly as possible. If the data from a run doesn’t look the way you were expecting – then do the procedure over again until those curves are well behaved and smooth. Make sure the loggers stay dry during the calibration – switching to spare dry housing tubes between the baths: Moisture is the greatest cause of failure in sensors and humidity/water always lowers the resistance of thermistors. If in doubt, let everything dry out for 24 hours before re-doing a calibration. Start your calibrations with a new coincell, as the voltage will droop significantly in the freezer.

Data Point #1: The freezing point of distilled water

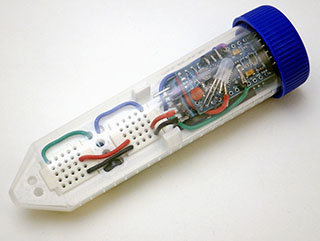

The most common method of obtaining a 0°C reference is to place the sensor into an insulated bucket of stirred ice slurry that plateaus as the ice melts. This is fine for waterproof sensors on the end of a cable but it is not easily done with sensors mounted directly on a PCB. So we immerse the loggers in collapsible 1200ml silicone food containers filled with distilled water. This is placed inside of a well insulated lunch box and the combined assembly is left in the freezer overnight, reading every 30 seconds.

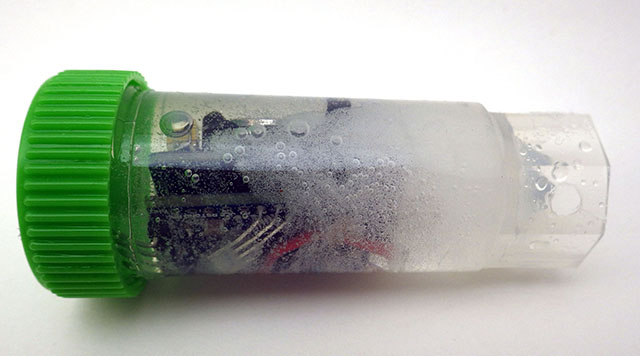

For the purpose of this calibration (at ambient pressure) we can treat the freezing point of pure water as a physical constant. So no reference sensor is needed on the logger while you collect the 0°C data. Leave the lunch box in the freezer just long enough for a rind of ice to form around the outer edges while the main volume of water surrounding the loggers remains liquid. I left the set in this photo a bit too long as that outer ice rind is much thicker than it needed to be for the data collection. Do not let the water freeze completely solid (!) as this will subject the loggers to stress that may crack the tubes and let water in to ruin your loggers.

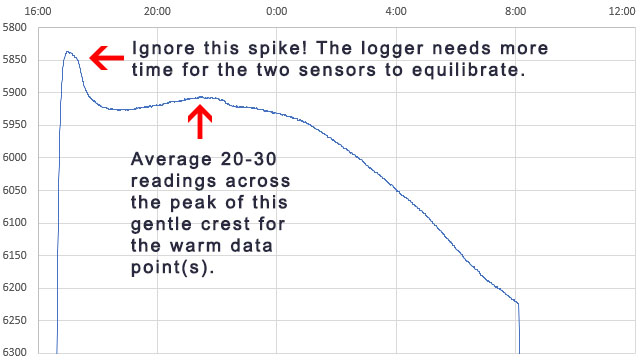

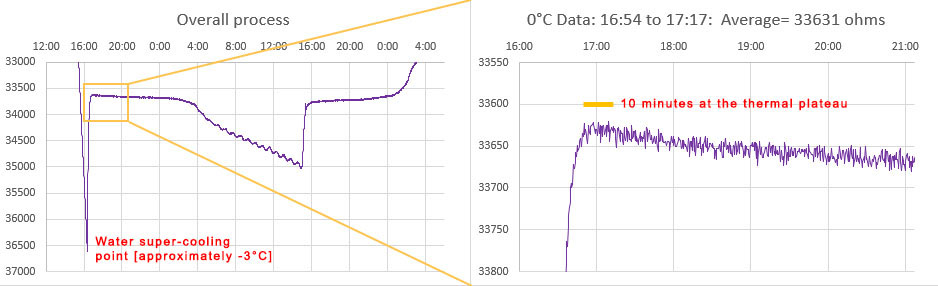

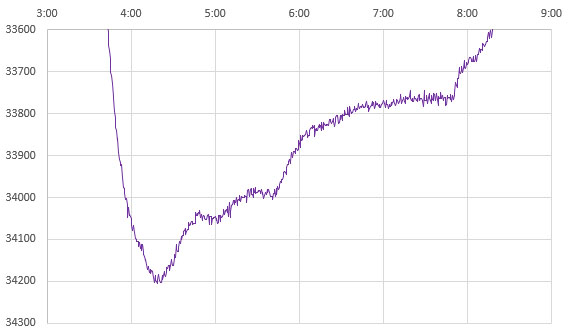

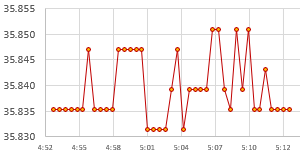

The trick is recognizing which data represents the true freezing point of water. Distilled water super-cools by several degrees, and then rises to 0°C for a brief period after ice nucleation because the phase change releases 80 calories per gram while the specific heat capacity of water is only one calorie, per degree, per gram. So freezing at the outer edges warms the rest of the liquid – but this process is inherently self-limiting which gives you a plateau at exactly 0°C after the rise:

Depending on the strength of your freezer, and the quality of the outer insulating container, the ice-point may only last a few minutes before temperatures start to fall again. An average of the NTC readings from that SHORT plateau immediately after the supercooling ends is your 0°C calibration point. This is usually around 33000 ohms for a 10k 3950 thermistor. Only the data immediately after super cooling ends is relevant and the box can be removed from the freezer any time after that event. I left the example shown above in the freezer too long but you have a reasonable window of time to avoid this. Once the freeze process initiates, it usually takes about 8 hours for the entire volume to freeze solid – after which you can see the compressor cycling as the now solid block cools below 0°C. You want to pull the sensors out of the freezer long before that solid stair-step phase (at 8:00 above)if possible.

If the supercooling spike is not obvious in your data then change your physical configuration to slow the cooling process until it appears. You want the inner surface of your silicone container to have smooth edges, as sharp corners may nucleate the ice at 0°C, preventing the supercooling spike from happening. Use as much distilled water as the container will safely hold -the loggers should be surrounded by water on all sides. It’s easier to do this whole process in a small domestic refrigerator rather than a powerful lab freezer because the process takes longer, and the water bath will spend more time at that ice point plateau.

Most refrigerators cycle based on how often the door is opened and those cycles can overprint your data making it hard to interpret. If you put a room-temperature box of water in the freezer between 6-7pm, it usually reaches the supercooling point around 2am, reducing the chances that someone will open the refrigerator/freezer door at the critical time. Even then, unexpected thermal excursions may happen if the freezer goes into a defrost cycle or an automatic ice-maker kicks in during the run. The time to reach that supercooling event can be reduced by pre-cooling the distilled water to ~5°C in the refrigerator before the freezer run. If any of the points on your curves are ambiguous, then do that run again, making sure the water is completely ice free at the start. Be prepared to do the overall procedure a few times to learn know how long your particular water bath / insulated container / freezer combination takes for the process.

As a technical aside, the energy released (or absorbed) during the phase change of water is so much larger than its typical thermal content that water based heat pumps can multiply their output significantly by making slushies.

Normalize your reference sensors to each other before you start using them to generate the warm/hot point data for your calibration. This catches any defective reference sensors or ones that have aged out of spec over time.

Data Point #2: Near 40°C

We have used the boiling point of water for calibration in the past, but the centrifuge tube housings would soften considerably at those temperatures. Ideally you want to bracket your data with equally spaced calibration points and 100°C is too far from the environmental conditions we are targeting. Heated water baths can be found on eBay for about $50, but my initial tests with a Fisher Scientific IsoTemp revealed thermal cycling that was far too aggressive to use for calibration – even with an added circulation pump and many layers of extra insulation. So we created an inexpensive DIY version made with an Arctic Zone Zipperless Coldloc hard-shell lunch box and a 4×6 inch reptile heating mat (8-10 watts). Unlike the ice point which must be done with distilled water, ordinary tap water can be used to collect the two warm temperature data pairs.

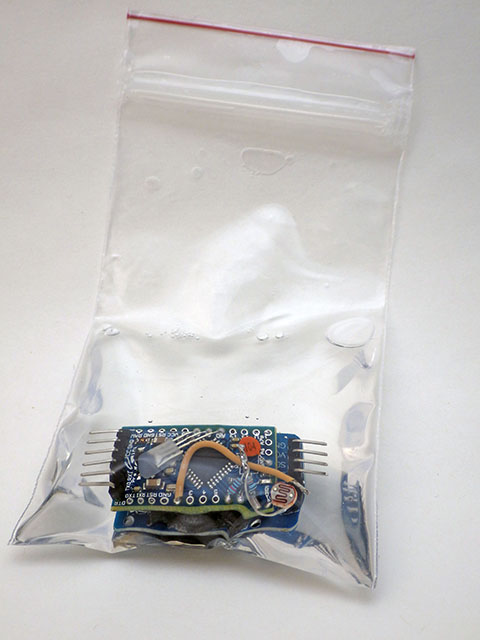

To record the temperature inside each logger, a Si7051 breakout module (from Closed Cube) is attached to the logger. A hold down of some kind must keep the logger completely submerged for the duration of the calibration. If a logger floats to the surface then air within the housing can thermally stratify and the two sensors will diverge. That data is not usable for calibration so the run must be done again with that logger.

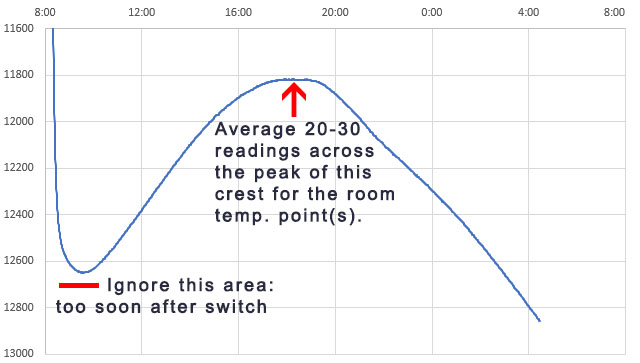

Data Point #3: Room Temperature

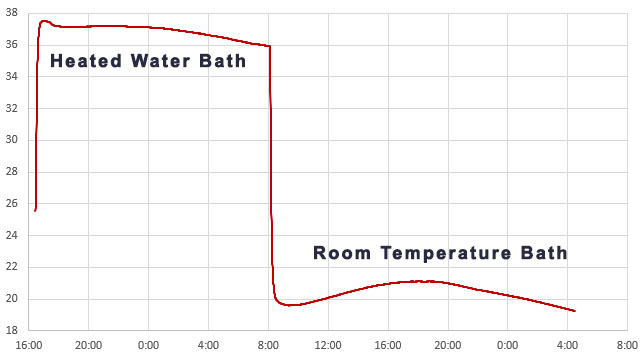

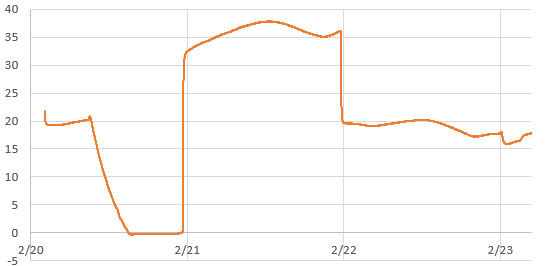

The loggers stay in the heated bath for a minimum of 4 hours, but preferably 8 -12 hours. The idea is you want the whole assembly to have enough time to equilibrate. Then they are transferred to an unheated water-filled container (in this case a second Arctic Zone lunch box) where they run at ambient temperatures for another 8 -12 hours. This provides the final reference data pair:

As the environment around the box changes, losses through the insulation create gentle crests or troughs where the lag difference between the sensors will change sign. So averaging several readings across those inflection points cancels out any lag error between the reference sensor and the NTC. Take care that you average exactly the same set of readings from both the Si7051 and from the NTC. At this point you should have three Temperature / Resistance data pairs that can be entered into the SRS online calculator to calculate the equation constants ->

The final step is to use those constants to calculate the temperature from the NTC data with:

Temperature °C = 1/(A+(B*LN(ohms))+(C*(LN(ohms))^3))-273.15

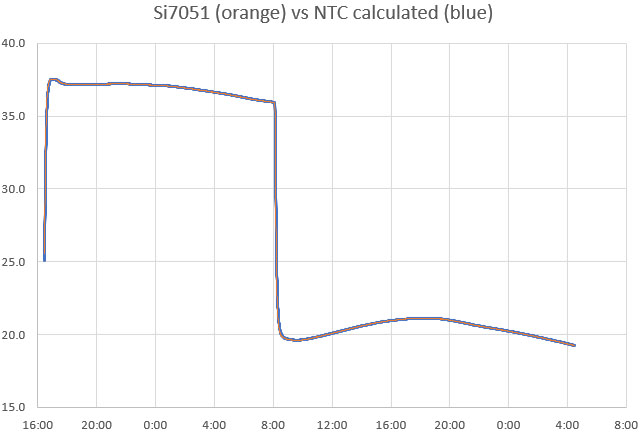

Then graph the calculated temperatures from the NTC calibration readings over top of the reference sensor temperatures. Provided the loggers were completely immersed in the water bath, flatter areas of the two temperature curves should overlap one another precisely. However, the two plots will diverge when the temperature is changing rapidly because the NTC exhibits more thermal lag than the Si7051. This is because the NTC is located near the thermal mass of the ProMini circuit board.

Note that any of the data pairs can be collected in separate runs. In fact, you could recapture any individual data pair and recalculate the equation constants with two older ones any time you suspect a run did not go smoothly. Add the constants to all of the data column headers, and record them in a google doc with the three reference pairs and the date of the calibration.

Validation

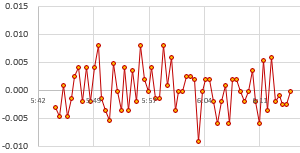

You should always do a final test to validate your calibrations, because even when the data is good it’s easy to make a typo mistake somewhere in the process. Here, a set of nine calibrated NTC loggers are run together for a few days in a gently circulating water bath at ambient temperature –>

Two from this set are a bit high and could be recalibrated, but all of the NTC temperature readings now fall well within the ±0.1°C expected from the Si7051 reference sensors we were using. This is a decent result from a method you can do without laboratory grade equipment, and the sensors could be brought even closer together by using this validation data to normalize the set.

Comments

The method described above uses equipment small enough to be portable, allowing easy classroom setup / takedown. More importantly this also enables the re-calibration of loggers in the field if you have access to a freezer. This makes it possible to re-run the calibrations and then apply compensation techniques to correct for sensor drift. Validating calibration before and after each deployment is particularly important with DIY equipment to address questions about data quality at publication time. Glass encapsulated NTC thermistors drift up to 0.02 °C per year near room temperatures, while epoxy coated sensors can drift up to 10x that. Our post deployment recalibrations usually see the ice point resistance of NTCs drifting by less than 100 ohms per year.

Having a physical constant in the calibration data is important because most of the affordable reference sensors in the Arduino landscape were designed for applications like healthcare, hvac, etc. So they are usually designed minimize error in warmer target ranges, while getting progressively worse as you approach 0°C. But accuracy at those lower temperatures is important for environmental monitoring in temperate climates. The method described in this post could also be used to calibrate commercial temperature sensors if they are waterproof.

Calibrating the onboard thermistor a good idea even if you plan to add a dedicated temperature sensor because you always have to do validation testing on a newly built logger – so you might as well do something productive with that burn-in time. I generally record as much data as possible during the calibration to fill the memory and flag potentially bad areas in the EEprom. (Note: Our code on GitHub allows only 1,2,4,8, or 16 bytes per record to align with page boundaries) . And always look at the battery record during the calibration as it’s often your first clue that a DIY logger might not be performing as expected. It’s also worth mentioning that if you also save the RTC temperatures as you gather the NTC calibration data, this procedure gives you enough information to calibrate that register as well. The resolution is only 0.25°C, but it does give you a way to check if your ‘good’ temperature sensors are drifting because the DS3231 tends to be quite stable.

For any sensor calibration the reference points should span the range you hope to collect later in the field. To extend this procedure for colder climates you could replace the ice point with the freezing point of Galinstan (-20°C) although a domestic freezer will struggle to reach that. If you need a high point above 40°C, you can use a stronger heat source. Using two of those 8 watt pads in one hard sided lunch box requires some non-optimal bending at the sides, but it does boost the bath temp to about 50°C. 3D printed PLA hold-downs will start to soften at higher temps so you may need to alter the design to prevent the loggers from popping out during the run.

If your NTC data is so noisy you can’t see where to draw an average, check the stability of your regulator because any noise on the rail will affect the Schmitt trigger thresholds used by our ICU/timer method. This isn’t an issue running from a battery, but even bench supplies can give you noise related grief if you’ve ended up with some kind of ground loop. You could also try oversampling, or a leaky integrator to smooth the data – but be careful to apply those techniques to both the reference and the NTC in exactly the same way because they introduce significant lag. Temperature maximums are underestimated and temperature minimums are overestimated by any factor that introduces lag into the system. In general, you want to do as little processing to raw sensor readings as possible at capture time because code-based techniques usually require some prior knowledge of the data range & variation before they can be used safely. Also note that our digital pin ICU based method for reading resistors does not work well with temperature compensated system oscillators because that compensation circuitry could kick in between the reference resistor and NTC readings.

And finally, the procedure described here is not ‘normalization’, which people sometimes confuse with calibration. In fact, it’s a good idea to huddle-test your sensors in a circulating water bath after calibration to bring a set closer together even though that may not improve accuracy. If you don’t have a circulating bath, you can create a test chamber by wrapping what you do have with foil-layer food delivery bubble bags. Creating post-calibration y=Mx+B correction constants is especially useful for sensors deployed along a transect, or when monitoring systems that are driven by relative deltas rather than by absolute temperatures. Other types of sensors like pressure or humidity have so much variation from the factory that they almost always need to be normalized before deployment – even on commercial loggers. Even if you don’t don’t carry through to a full normalization the water bath huddle-test will catch errors you may have made during your calibration. With all the averaging, copying, etc. during this multi step procedure, it’s easy to make a typo/mistake somewhere along the way and you really don’t want to discover those after a deployment.

References & Links:

SRS Online Thermistor Constant Calculator

Steinheart & Heart spreadsheet from CAS

S&H Co-efficient calculator from Inside Gadgets

Molex Experimenting with Thermistors Design Challenge

Thermistor Calibration & the Steinhart-Hart Equation WhitePaper from Newport

ITS-90 calibrates w Mercury(-38.83), Water(0.01) & Gallium(29.76) Triple Point cells

Guide on Secondary Thermistor Thermometry, White et al. (2014)

Precise Temperature Measurements guide from Texas Instruments

Steinhart-Hart Equation Errors BAPI Application Note Nov 11, 2015

The e360: A DIY Classroom Data Logger for Science

How to make Resistive Sensor Readings with DIGITAL I/O pins

Single Diode Temperature Sensors

Measuring Temperature with two clocks

How to Normalize a Set of Sensors