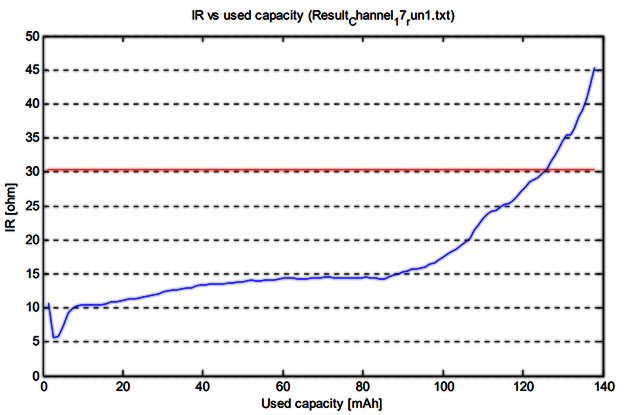

Reviewers frequently ask us for estimates based on datasheet specifications but this project is constantly walking the line between technical precision and practical utility. The dodgy parts we’re using are likely out of spec from the start but that’s also what makes our 2-module data loggers cheap enough to deploy where you wouldn’t risk pro-level kit. And even when you do need to cross those t’s and dot those i’s you’ll discover that OEM test conditions are often proscribed to the point of being functionally irrelevant in real world applications. The simple question: “How much operating lifespan can you expect from a coin cell?” is difficult to answer because the capacity of lithium manganese dioxide button cells is nominal at best and wholly dependent on the characteristics of the load. CR2032’s only deliver 220mAh when the load is small: Maxell’s datasheet shows that a 300 ohm load, for a fraction of a second every 5 seconds, will drop the capacity by 25%. However, if the load falls below 3μA for long periods, then this also causes the battery to develop higher than normal internal resistance, reducing the capacity by more than 70%. The self-discharge rate increases with temperature due to electrolyte evaporating through the edge seal. Another challenge is ambient humidity which can change PCB leakage currents significantly.

Surprisingly little is known about how a CR2032 discharges in applications where low μA level sleep currents are combined with frequent pulse-loads in the mA range; yet that’s exactly how a datalogger operates. As a general rule, testing and calibration should replicate your deployment conditions as closely as possible. However, normal run tests take so long to complete that you’ve advanced the code in the interim enough that the data is often stale by the time the test is complete. Another practical consideration is that down at 1-2μA: flux, finger prints, and even ambient humidity skew the results in ways that aren’t reproducible from one run to the next. So a second question is “How much can you accelerate your test and still have valid results?” Datasheets from Energiser, Duracell, Panasonic and Maxell reveal a common testing protocol using a 10-15kΩ load. So continuous discharges below 190μA shouldn’t drive you too far from the rated capacity. Unfortunately, that’s well below the 3-400 ohm loads you get with cheap battery testers, or videos on YouTube, so we are forced yet again to do our own empirical testing.

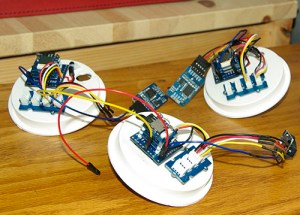

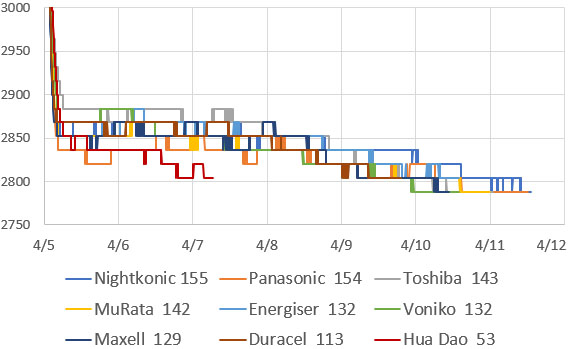

The easiest way to increase our base load is to leave the indicators on: all three LEDs will add ~80μA to the sleep current when lit using internal the pullup resistors. 80μA is ~16x our normal 5μA sleep current (including sensor draw & RTC temp conversions). A typical sampling interval for our work is 15min so changing that to 1 minute gives us a similarly increased number of EEprom save events. With both changes, we tested several brands to our 2775mv shut-down:

| Brand | Run Time (h) | Cost / Cell | | | Brand | Run Time (h) | Cost / Cell |

| Panasonic | 1500 | $ 1.04 | | | Duracell | 1298 | $ 1.81 |

| Voniko | 1448 | $ 0.83 | | | AC Delco | 1223 | $ 0.79 |

| Maxell | 1444 | $ 0.58 | | | Nightkonic | 1186 | $ 0.24 |

| Toshiba | 1325 | $ 0.64 | | | MuRata | 1175 | $ 0.45 |

| Energiser | 1307 | $1.28 | | | Hua Dao | 642 | $ 0.14 |

Despite part variations these batteries were far more consistent on that 20ohm plateau than I was expecting. This ~15x test gives us a projected runtime of more than two years! That’s twice the estimate generated by the Oregon Embedded calculator when we started building these loggers. We did get a 30% delta between the name brands, but these tests were not thermally controlled and we don’t know how old the batteries were before the test. The rise in voltage after that initial dip is probably the pulse loads removing the passivation layer that accumulates during storage. The curves are a bit chunky because the 328P’s internal vref trick has a resolution of only 11mv, and we index-compress that to one byte which results in only 16mv/bit in the logs.

One notable exception is the Hua Dao cells, which I tested because, at only 14¢ each, they are by far the cheapest batteries on Amazon. My guess they are so cheap because they used a lower grade of steel for the shell which increases the cell resistance. We have many different runs going at any one time, and to make those inter-comparable you need to start each test with a fresh cell. Even if the current run test doesn’t need a batteries full capacity sometimes you just need to eliminate that variable while debugging. You also use a lot of one-shot batteries for rapid burn-in tests so it makes sense for them to be as cheap as possible. Now that I know Hua Dao delivers half the lifespan of name brand cells, I can leverage that fact to run some of those tests more quickly. I had planned on doing this with smaller batteries but the Rayovac Cr2025 I tested ran for 1035 hours – longer than the Hua Dao Cr2032!

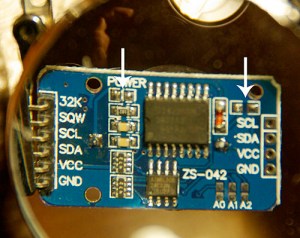

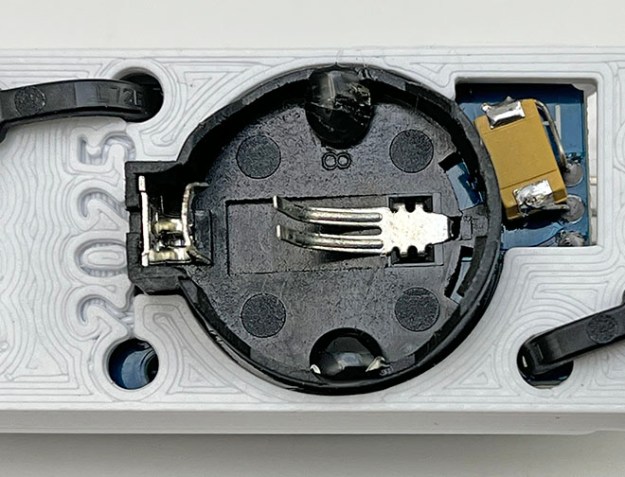

Testing revealed another complicating factor when doing battery tests: With metal prices sky-rocketing, fake lithium batteries are becoming more of a problem. We’ve been using Sony Cr2032’s from the beginning of the project but the latest batch performed more like the Hua Dao batteries. This result was so unexpected that I dug through the bins for some old stock to find that the packaging looked slightly different:

On closer inspection it didn’t take long to spot the fraud:

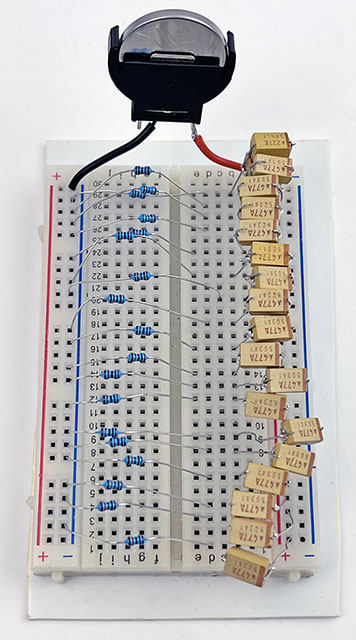

More tests are under way so I’ll add those results to this post when they are complete. A couple of the 80μA units have been re-run after removing the 227E 25V 220μF rail buffering caps, confirming that the tantalum does not extend overall run time on good batteries very much because their internal resistance rises slowly, but rail caps can more than double the lifespan with poor quality batteries like the Hua Dao. In my 5min tests at 3 volts, [477A] 10v 470μF caps fell to a leakage of about 160nA or about 3x more than the 60nA on a [227E] 25v 220μF tantalum. After leaving them connected (through a 4k7 limiting resistor) on a breadboard for 24 hours the 470uF fell to only 30nA and the 220uF fell to 20nA. 6v volt [108J] 1000μF rail caps have much higher 980nA leakage which is larger than the DS3231’s typical constant Ibat of 840nA. This shortens overall logger runtime to only 6-7 months: so very large rail caps are only useful with high drain sensors or in cold conditions.

Very old tantalum capacitors like the ones you get from eBay may require a resistor-limited “reforming” process to restore their dielectric or you could see high leakage because of damaging inrush currents when they are first connected to power. I now pretreat my tantalums by connecting them through a 10k limiter, and letting them just sit in that state for at least 24 hours before using them. Usually the caps just sit on the breadboard (shown here) until I’m ready to use them…sometimes for a couple of weeks.

A startup-shorted tantalum can have leakage currents as high as 10uA which scuppers your low current device.

Northern caves hold near 5-10°C all year round, so the current set is running in my refrigerator. I will follow that with hotter runs because both coin cell capacity AND self-discharge are temperature dependant. We also plan to start embedding these loggers inside rain gauges which will get baked under a tropical sun .

Addendum 2023-08-01

This summers fieldwork required all of the units in my testing fleet so I only have a handful of results from the refrigerator burn down tests [@5°C]. The preliminary outcome is that, compared to the room temperature burns, the lithium cell plateau voltage lowers between 80-100mv (typically from 3000mv to 2900mv). Provided the loggers were reading a low drain sensor the ‘cold’ lifespan was only about 20% shorter because the normal 50-70mv battery droop (during sensor reading / eeprom save) only becomes important after the battery falls off its plateau. This is approximately the same lifespan reduction you see running at room temp without a rail buffering capacitor – as the buffer also only comes into play when the battery voltage is descending. This is also the reason why the larger 1000μF rail capacitors usually only provide about 10% longer life than the 220μF rail caps as the reduced battery droop with the larger cap only comes into play when the cell is nearing end of life. Net result is that increasing to 1000μF rail buffers almost exactly offsets the lifespan losses at colder ambient temps to 0°C . But for longer deployments, at normal room temps, the 1-2μA leakage of a 6v 1000μF [108j] tantalum removes any advantage over the 25v 220μF [227e] which has only 5nA leakage at 3 volts. Also note that some caps seem to need a few hours to ‘burn in’ before they are saturated enough to measure their leakage properly.

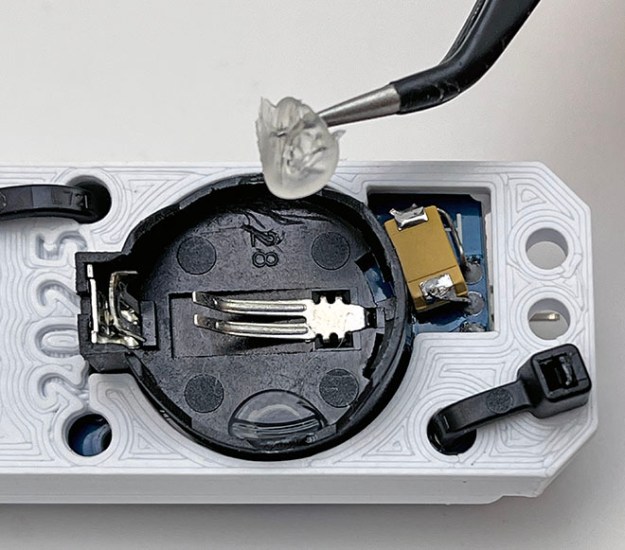

Weak battery springs, or sloppy plastic moulding on the RTC module can make a logger vulnerable to bumps that disconnect power (causing the logger to shut down). Most of the time the battery can be secured reasonably well by simply by laying a line of hot glue along the top edge opposite the positive contact spring. This is easily removed after the deployment:

Occasionally you get an RTC module with a battery holder loose enough that the coin cell can actually rock from side to side, pivoting on the negative contact spring. This more extreme loose battery case requires two drops of glue under the coincell:

The freezer results are an entirely different situation where are only seeing a few days of accelerated 100μA sleep current operation because once you get below -17°C the voltage starts to droop below our 2800mv shutdown voltage during EEprom saves. So the logger only operates for the brief span of time where the initial overvoltage on new Cr2032 is still above its nominal plateau voltage. For truly cold weather deployments you’d need a different battery chemistry like lithium-thionyl chloride (LiSOCl2) which is good to -40°C provided you add a large rail buffering capacitor to compensate for it’s current limitations. Loggers drawing the normal 2-5μA sleep current should still run OK in a domestic freezer provided the sensor is not too demanding – but that’s about the practical limit for these loggers. In fact we use waters 0°C phase transition as a reference when calibrating the onboard thermistors – and that’s done on a normal CR2032.

Addendum 2025-01-25

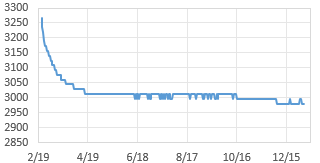

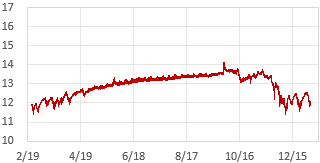

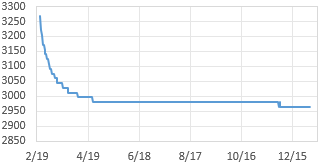

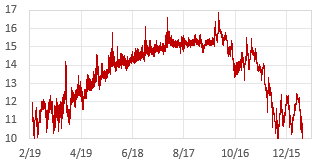

Finally getting the 2024 deployments swapped out, so I have some real-world burn down curves to add here. These units were in a U.S. cave rather than our typical Mexico field sites, so temps were cool enough to have some effect on the cell voltage:

With normal runtime operations the CR2032s plateaued near the nominal 3v with a 220µF rail buffering cap. It’s hard to tell if that slight shift indicates the end of the batteries 20ohm plateau or was just a response to the lower winter temperatures. Assuming that was the end of the plateau, then I’d expect another three (?) months of operation before the internal resistance pushes the voltage droop during EEprom saves to our 2800mv cutoff. Both were deployed with 1 gram of desiccant, which probably was not enough for the 30mL polypropylene tubes (given the color of the indicator beads when the loggers were downloaded). Unsaturated silica gel holds the air near 20%, but these loggers probably spent half of their deployment at high RH. I rarely put desiccant in my testing loggers and on the rare occasion when I forget one of them long enough for the Cr2032 to fall below 1000mv there is “a particular smell” that is quite noticeable when the logger is opened. That makes me wonder if electrolyte off-gassing also affects the color of the desiccant indicators beads.

The take home lesson is: when your accelerated testing indicates a two year lifespan under optimal conditions, you should expect to reach only half of that on a real-world deployment. If I assume a 3.5µA sleep current (ie: the DS3231’s timekeeping average incl. TXCO conversions) with four 3.5mA x 50msec logging events per hour, then the Oregon Embedded calculator gives me an 100mAh battery life of 958 days. Interestingly, the capacity of a 256k EEprom @ 15min interval storing 4bytes/record is also about 680 days. Taken together, these factors mean our loggers should only be expected to operate for a year – plus – a healthy 3-6 month margin if you used a good Cr2032 battery. It’s also worth looking at how many I2C transactions you are doing per record as they can add significant CPU runtime. At the 100khz default each byte takes ~100 µs, and a typical sensor transaction will easily exchange ten bytes.

One unknown variable is the self-discharge rate of the Cr2032. I’ve seen references to a nominal 1% loss in battery capacity per year under ideal conditions, which would be like adding another 300nA of continuous load. But that loss can be up to 10x larger in high humidity environments. To minimize capacitor leakage current, try choose caps with a voltage rating that’s 3x larger than the expected operational range.

Another variable that can have a serous impact on lifespan is the number of EEprom save events per day. In my tests a typical EEsave uses between 0.3-0.5 milliamp seconds of power, with sensor readings using a similar amount/record. (in comparison to a ‘good’ loggers sleep-current baseload of about 250-300 milliamp-seconds per day) So a few hundred EEsave events could potentially use power comparable to the sleep current each day. EEproms have to erase and re-write an entire page of memory any time you save a number of bytes less than the hardware page size. If you increase the two wire library buffers, and pre-buffer the sensor data into temporary arrays, you can increase the bytes per EEsave event from 16 to 64 (or even 128) to reduce the number of save events. When you transfer the same number of bytes as the EEproms hardware page size then the chip can skip any ‘pre-erase’ steps entirely – cutting ALL save events to 1/2 the time/power they would use saving a smaller number of bytes. This both increases speed and can extend operating lifespan significantly with multi sensor configurations collecting many bytes of data per record over short 1-5 minute sampling intervals.

Links & References:

Evaluating Battery Models in Wireless Sensor Networks, Rohner et.al.

ATmega328 Calculation Speed tables