Addendum 2017-02-20:

Addendum 2017-02-20:

This original $10 DIY Arduino logger page was posted in 2014, and there have been several significant updates to the way I assemble the basic three component design since the early version described in the post below. If you are building your first data logger you might want to start with the new one-hour build: ☀ 1-hour Pro Mini Classroom Datalogger ☀ Most importantly, as the build achieved lower and lower sleep currents, I stopped using the Pololu power switch described below, as it ended up using more power than the sleeping loggers themselves.

Also note: The Pololu power switch described in this post has been superseded by the vastly superior Adafruit TPL5110 Low Power Timer. Cfastie has been putting this board through it’s paces over at PublicLab.org.

Original post from 2014-10-07:

Here is the latest version of my basic DIY datalogger, which adds a new component to the design:

Note: There is a set of detailed build instructions for a pro-mini based data logger from this plan at: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

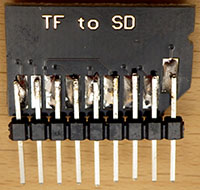

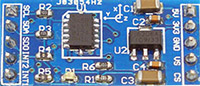

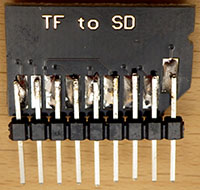

Note: Adapter pin numbering follows this document: 1 = Chip Select, 2=Data in = MOSI, 3 = GND, 4 = VDD (supply voltage, not > 3.3v!), 5 =SCLK , 6 =GND , 7 =Data out =MISO

Several sources recommend pullups on CS, MOSI, MISO and SCK, though the loggers will usually work ok without them. But testing has shown that some SD cards take a very long time to go to sleep unless CS, MOSI & MISO are also pulled up.

The addition of the power switch solves the last nagging problem I had with the original 3-component design: unpredictable system behavior when the power supply goes low. I knew from my bench tests that some boards (like the Rocket Ultra pictured here) gracefully go into a kind of holding state till they completely brown out, while others go into a kind of power cycling loop, alternating off & on, when the battery voltage gets too low for the regulators. Now, you can just read the divider and drive the control pin high to shut down the entire system. Of course, everything is a trade-off, and this soft switch almost doubles the sleep current, from ~0.35 mA (with a good SD card!) to ~0.6 mA. Assuming 2000 usable mAh per AA, this brings my “back of the envelope” estimate down to 4-6 months on three cells (my design goal is of 1 year of operation). But given all the uncertainties I have dealt with regarding μSDcard power drains, battery leaks, and the rough and tumble of real world deployments, I think I will pay that price to protect my data. It’s not always that easy to get back into those caves on schedule. On future builds, I will try to find a simple latching relay circuit to get back the capacity I’m losing with the Pololu switch.

The SD card debacle forced me to make my first breadboard version of these loggers to measure power consumption at the component level . All my previous builds were soldered, and now that I know how fast bread-boarding is (~45 min , mostly for soldering the header pins) I realize that was a mistake.

And I also finally got around to posting the drip logger script for this platform on the project’s Github. Even though the drip sensors only use an ADXL345 (for now), I left in all the other sensor support developed for the flow monitors, as the system is meant to be easily adapted to other applications. I also have two different versions of sleep code buried in there, one with the Rocket Scream low power library, which shuts off the BOD, and the other which just uses a variable WDT timer to wake from sleeps while the fuses are left on. I still have not decided if I am comfortable with BOD fuse shutdown in a data logger application. With a 10k limiter keeping the led current low, I sometimes leave the indicator pips on during sleeps without impacting the power budget too much. If you change the limiter to make the led brighter, make sure you shorten the time that the led is left on.

From the beginning I have focused on creating a fully functional data acquisition system from a small number of preexisting modules. Only interchangeable, non-proprietary components and formats are being used (AA batteries, csv files, SD cards, etc.) because I want my logger to have the flexibility of replacing any individual component with half a dozen other parts that are readily available. To give some sense of this, I have compiled a “budget” and a “preferred” parts list:

Budget Parts:

| Component |

Comment |

Cost |

|

*Clones work, but the “real” Sparkfun ProMini boards give me trouble with the SD cards. I suspect that a 22uF decoupling cap between the SD card’s Vcc<->Gnd lines might help the MIC5205 cover the current peaks.

|

3.3v ProMini clone*: And occasionally you catch them for <$2.50 on eBay. Make sure Vreg is 150mA or more, and watch for Vcc> 3.3v. Usually 0.05-0.2 mA > sleep currents than Rocket Ultra boards, pin layouts can be irritating, remove power leds & inspect solder joints very carefully. It’s worth noting that you can bypass the onboard regulator, and use an external MCP1700 vreg. |

$4.00 (+guilt) |

|

RTC modules: wash them as they are often covered with blobs of leftover flux, remove charging circuit & pwr led resistors. Check my RTC page for further info on these modules. |

$1.50 |

|

Micro SD card adapter: try to get the ones that have Molex connectors, you need to leave room for the flap in your design, or you could try the self-spring type but these don’t seem to hold up to the soldering heat as well. If you hear a “snap” during soldering, start over – you killed one of the spring contacts. |

$1.00 |

|

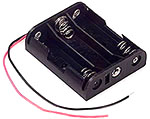

3 x AA Battery Holders: and don’t forget the connectors! I usually go for the deans style knock-offs, but expect to throw more than a few of them out due to bad alignment. You need a good soldering iron to use them. |

$1.50 |

|

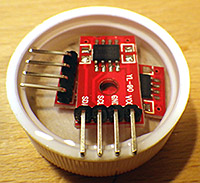

3 color LED module: The old round-style Keyes modules are the brightest I have found so far with a 10k limiter. You could buy raw common cathode leds for less, but I find the little breakout boards make it easier to mount them with JB plastiweld putty. |

$1.00 |

|

There are so many different pre-built waterproof boxes out there to choose from I’ve lost count. If you build your own from PVC, you can make them far more rugged. |

$3.00 |

|

The Muve Music cards are the only ones I have found that are usually authentic when I get them on eBay. My longest logger runs to date (5 months) have generated less than 50Mb of CSV data. So 1 gig is plenty. Test your SD cards extensively before any deployment to make sure they go to sleep properly! |

$2.00 |

|

You will need at least one serial adapter, and I usually bring several for fieldwork. CP202’s are cheap but don’t work as well for me as FTDI’s. Be sure to get 3.3v and note that Windows drivers will brick fake FTDI’s |

$2.50 |

| Adafruit sells 26awg silicone wire in 2m lengths. Perfect for starting a new project without breaking the bank. Deans micro plugs are the best connectors I have found and they are available from 2 to 6 pins. |

Resistors, wires, heat shrink, etc. The cheapest stuff I have found so far is at Electrodragon, but you get what you pay for wrt quality & 3 week delivery times. |

$1.00 |

Preferred Parts:

When the budget isn’t too tight, I splash out for better components. After you build a few, and go through the effort to install them, you will start to realize that your time is worth more. Certainly your data is. But I would still make your first few builds with cheaper stuff, at least till you feel confident putting them together. Cable routing inside a housing is important, and it usually takes me a few tries before I get the physical build sorted out.

| Component |

Comment |

Cost |

|

The Rocket Scream Mini Ultra wins over other mini format boards with lower sleep current & 100 mA more juice at the high end. I also like the layout, which has an extra ground pin available for the voltage divider. 1284P’s like the Moteino MEGA (+built in RF!) are looking interesting, but I have not had a chance to play with them yet. |

$14.00 |

|

The Chronodot is still my gold standard as a trustworthy RTC. But using it takes more space, and requires a separate EEprom. Of course that allows you to go up to a 256k AT24C256 possibly eliminating the SD card. Or try a little FRAM for faster writes. And for only $33 more you could go all the way to a FE-5680A atomic clock but good luck fitting that into your housing 🙂 |

$17.00 |

|

I trust Adafruit’s quality control. This board lets me tuck the SD under the RTC in tight builds if I use 15mm M2 standoffs. |

$2.50 |

|

Battery holders: Heavy duty aluminum holders from Keystone Electronics are my 1st choice. 3xAA 147’s are good, but singles give you more layout options. Don’t forget isolation diodes if you have multiple banks. |

$4.00 |

|

I’m putting the Pololu Pushbutton Power switch in the “preferred” list because it’s not required and it adds 0.3 mA to the sleep current – that’s more than the logger itself! |

$6.00 |

The rubber flexes quite a bit under water and I have only tested these caps to about 5 m depth. |

Waterproof Housing: 4″ PVC sewer drain cap, 4′ knockout cap to mount logger components inside & a Fernco Qwick Cap. I mount the LEDs & sensors in short lengths of 3/4 pipe which are solvent welded to the exterior, then filled with Loctite E30CL. |

$6.00 |

|

I like these tiny JY-MCU ‘s when I have a design that is really tight on space. But getting a particular 5050 is not easy on eBay due to unreliable vendors. |

$1.50 |

|

My current favorite wire is Adafruit’s 26awg with Turnigy silicone & Cal Test Electronics Test Lead Wire also being good. Stiff PVC insulation gets irritating when you are trying to route wires into small housings. |

$2.00 |

|

Most of my builds go under water, so the sensors get potted into place on the housing. An interconnect system like the I2C hub from Groove Studios makes the “sensor caps” interchangeable. |

$3.00 |

|

These Sparkfuns are still my favorite serial adapters, they always seem to work, and the new pin connectors work are more robust. |

$15.00 |

Well, there it is: the simplest fully capable datalogger I could come up with. You have from 3 to 5 analog lines free depending on your board (1024 levels on the ADC), and two digital lines left for your 1-Wire sensors (and you still have a free interrupt line on pin 3, and the analog pins can be used identically to the digital pins, using the aliases A0, A1, etc) . I2C is already pulled-up (4.7k) & broken out for you on the RTC cascade port. SPI is still available if you watch your timing with the SD communication. (Both get SCK, MISO, and MOSI in parallel, But each device needs its own Chip Select line, as you can only communicate with one device at a time : SoftwareSPI is also an option but it looses the speed advantage). If you need better resolution on your ADC, you can add an ADS1015 to add four more 12 bit channels. If you need more output lines, you can look into adding a shift register, and there are plenty of transistor/relay breakouts if you want to control high power loads or LEDs.

Once you have a unit up and running, don’t forget to give the boards (but not the μSD adapter) a good dash of silicone conformal coating before they go into the field. And it never hurts to throw a desiccant pack or two in there while you are at it.

——————————————————————————————–

Addendum 2014-10-09:

I tested two breadboard builds (configured as drip sensors) to get a sense of the current draw of the individual components. Without the power switch, the ProMini clone logger drew a sleep current of 0.26 mA sleeping in powerdown mode using RocketScreams Low Power Library with ADC & BOD off.

ProMini clone +

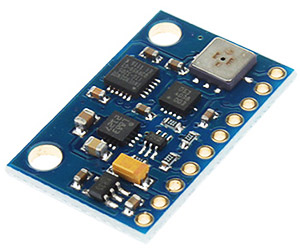

Adxl345 accelerometer (50 hz, power save mode) : 0.058 mA

Sandisk 256mb uSD card : 0.061 mA

DS3231 & AT24c32 eeprom combo (with 4.7k pullups) : 0.089 mA*

* I also tested an AT24c256 separately with a chronodot RTC, 10k pullups, and that eeprom draws about 0.03 mA when not being accessed. As you might imagine, I will be examining the RTC very carefully, as 0.089 mA is much higher than I would have expected for something that is supposed to run off of a coin cell. (The datasheet actually specifies a standby supply current of 0.11 mA at 3.3v)

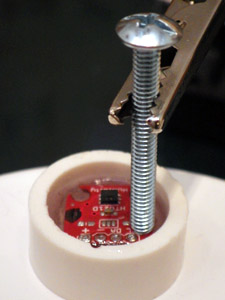

Double length header pins make it easier to breadboard the SD card. DO NOT TAKE TOO LONG to solder jumpers onto any of these adapter boards. If the springs mounted inside re-flow from excess heat, the connections are toast.

Subtracting those figures from 0.26 mA indicates that the ProMini clone with its MIC5205 regulator uses about 0.052 mA when the unit is sleeping. I am guessing that most of that is due to losses on the regulator, since it is still providing power to the above components.

Then I changed over to a RocketScream Ultra board, and the whole logger drew 0.22 mA with the same SD card, indicating that “sleeping” logger overhead with their MCP1700 regulator is around 0.012 mA. Significantly better than the 5205 based system, and you have another 100 mA of current capacity at the top end.

I then tested that Rocket ultra unit with the Pololu power switch in the circuit, and sleep current went up to 0.53 mA , indicating that the switch is adding 0.32 mA to the sleep current for this design (after I removed it’s power on LED). Just to be sure about this I measured the current on the other side of the Pololu switch, and the logger unit was still drawing 0.22 mA, so it was not noise, or some other weird side effect keeping the SD card from sleeping properly.

Addendum 2014-11-28

A month long test of one of these units binning at 15 minute intervals, with the Pololu installed (0.56mA sleep current) lowered the 3xAA power supply voltage by 181 mV. Being conservative, this means we will only get about 4 months of run time with the no-name alkaline batteries I used. That’s a pretty dramatic reduction of run time for that one extra component so I probably will not be using the Pololu switch for my longer term deployments. Field test results so far indicate that a unit sleeping at 0.30 mA will deliver between 6-9 months of operation on a 3xAA battery pack.

Addendum 2015-01-20

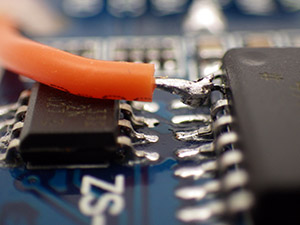

Just thought I would post a quick shot of how I jumper the pullup on that SD card adapter with the legs of the resistor itself. Super thin 30 AWG wire makes jumpering the ground line much easier as well. Once all the jumpers are on, I clean off leftover flux with 90% isopropl alcohol, and then coat the contacts with silicone conformal coating, being careful not to let it run to the other side of the board where it would block the connections. Then I adhere the boards to the platform with double sided tape, which has been working surprisingly well on ABS knockout caps.

Just thought I would post a quick shot of how I jumper the pullup on that SD card adapter with the legs of the resistor itself. Super thin 30 AWG wire makes jumpering the ground line much easier as well. Once all the jumpers are on, I clean off leftover flux with 90% isopropl alcohol, and then coat the contacts with silicone conformal coating, being careful not to let it run to the other side of the board where it would block the connections. Then I adhere the boards to the platform with double sided tape, which has been working surprisingly well on ABS knockout caps.

It is also worth mentioning that the Green channel on the multi color common cathode LED’s is so much brighter than the red & blue colors (4000mcd vs 8-900 mcd), that you can actually use two limiting resistors – one 10K on the common ground line, and an extra 20K on the green line. In fact, if you can live with a really faint indicator led, you can take the limiters to 20/40K or more if your LED is bright enough. You don’t want to waste too much power on indicator LEDs when no one is around to see them, and this brings the green channel down to 110uA, while leaving the red & blue channels bright enough to see. Luke Miller has an elegant method using a magnetic reed switch interrupt to enable & disable his status LED’s to save power, but I often need all the interrupt lines for my sensors. I could probably work around this with a pin-change driven interrupt, but have not had a chance to dig into that yet.

It is also worth mentioning that the Green channel on the multi color common cathode LED’s is so much brighter than the red & blue colors (4000mcd vs 8-900 mcd), that you can actually use two limiting resistors – one 10K on the common ground line, and an extra 20K on the green line. In fact, if you can live with a really faint indicator led, you can take the limiters to 20/40K or more if your LED is bright enough. You don’t want to waste too much power on indicator LEDs when no one is around to see them, and this brings the green channel down to 110uA, while leaving the red & blue channels bright enough to see. Luke Miller has an elegant method using a magnetic reed switch interrupt to enable & disable his status LED’s to save power, but I often need all the interrupt lines for my sensors. I could probably work around this with a pin-change driven interrupt, but have not had a chance to dig into that yet.

Addendum 2015-02-12

I just wanted to add a link here to my new pvc housing design. While not quite as simple as the rubber quick cap housing pictured in the table above, I am certain that this Formufit table-cap based design is the simplest diy housing you could build that will go to significant depth under water.

Addendum 2015-04-14

On my logger I use a voltage divider to monitor the main battery. This bleeds a few μA, but given the overall sleep current that’s a small price to pay for the simplicity of using two resistors & a cap to do the job. However I just stumbled across a very good way to monitor the battery voltage with virtually no loss over at the LowPowerLab blog. About half way down the discussion user JC suggests ” a resistor divider network, with the high side gated by a FET. Turn the FET on when you want to read the battery voltage, off the rest of the time. The leakage is somewhere down in the femtoamps.” Another elegant solution for me to look into if I ever get this project to the stage where I am actually implementing elegant solutions.

Addendum 2015-06-28

It will be a while before I sort out all the details of the V3 logger platform, but for a preview of what might be coming, you can see a couple of builds currently on the test bench here. Also, after many successful field deployments without the power switch where the batteries died but the SD card data was still intact, I have dropped the Pololu power switch from the design. I just could not afford to loose all that power.

Addendum 2015-10-24

I have produced a set of detailed build instructions for a pro-mini based version of this data logger which can be found at:

- Part 1 (component preparation)

- Part 2 (logger platform assembly)

- Part 3 (housing assembly)

I still prefer to use the rocket ultra as it’s voltage regulator is more efficient, but it is still possible to build a decent logger with the minis that should sleep below 0.25mA.

Addendum 2016-01-25:

Reliable sources recommend pullups on the SPI lines, though I have been running my loggers for a long time without them. I have noticed that some SD cards take a really long time to go to sleep unless CS, MOSI & MISO are pulled up, and some just refuse to sleep at all without the pullups. These weak pullup resistors are not described in this tutorial. If you already have loggers built without them, there is a workaround using the 328’s internal pull-up resistors that I current have in testing. Despite the fact that only CS requires it, I found that all three lines had to be pulled up before misbehaving cards went to sleep properly. So add these lines to the beginning of your setup before you run sd.begin

// pulling up the SPI lines

pinMode(chipSelect, OUTPUT); digitalWrite(chipSelect, HIGH); //pullup the CS pin

pinMode(MOSIpin, OUTPUT); digitalWrite(MOSIpin, HIGH);//pullup the MOSI pin

pinMode(MISOpin, INPUT); digitalWrite(MISOpin, HIGH); //pullup the MISO pin

delay(1);

It’s worth noting that there is some debate about the utility of this approach. Because SPI is a complex protocol, adding internal or external pullups could actually prevent you from being able to use other SPI sensors with your data logger. That is one reason why I tend to stick to I2C & analog sensors on my builds, so the SPI lines are dedicated to the SD card only.